Hey, all. April here again.

In the last blog, I mentioned that we were eager to get started using Second Intention Farm’s Jimmy Red corn and springwater to make our own craft whiskey. But we haven’t built our building yet, and without a bonded premise, we can’t yet get our DSP (Distilled Spirits Permit). But there IS another option that fledgling distillery’s use all the time to get products in the queue before they have their own setup. That option is contract distilling.

Last fall, knowing we still had an abundance of corn from the previous year that was literally in the way of the critical project of building our distillery, Chip came up with an excellent way to solve both problems at once. We’d get someone else to turn the farm’s corn and springwater into whiskey and barrel it for us until we could legally store it ourselves on our own premises. It takes four years to age a bourbon and contract distilling would allow us to start that process at least two years sooner.

When it comes to contract distilling there are a whole lot of options. Some distilleries will buy a spirit outright that has already been aged and just put it in a bottle with their label on it (one distillery we know of famously won awards for their bought whiskey before they’d even put a shovel in the ground to build their own). Others will supply the contract distillery with a mash bill they want made to order. In that case, the contract distillery will usually use whatever suppliers they are accustomed to using for their own products.

There are many distilleries that offer contract distilling, since a still that isn’t running isn’t making any money. But for what we had in mind, we knew it would have to be someone local. It was our plan to not only use the mash bill we’ve been testing out for a while now, but to provide the farm’s springwater and heirloom Jimmy Red corn to make it. And we didn’t want to have to transport those materials very far, since we’d be doing it ourselves.

There are several distilleries not too far away from our farm. One of those is Prichard’s Distillery in Fayetteville. We’d met with Mr. Prichard earlier in the year to discuss buying some equipment from him he no longer needed. So we reached out to him about our contract distilling plans. After a little back and forth, a deal was struck and we signed the contract last November.

Now, we just had to finish shucking, shelling, cleaning and milling about 3 ½ tons of corn!

By early December, we had processed and milled – using the hammer mill our miller loaned us – enough corn for the first run, 1500 pounds. We were still in the midst of a severe drought, so collecting the springwater we needed took much longer than we’d anticipated. But by mid December, everything we needed was at Prichard’s, including the barley and wheat we’d purchased from Middle Tennessee’s sole malt barn, Batey Farms, near Murfreesboro. We were ready to cook.

We’ve covered that whole process extensively on our socials. The first day we cook the corn, add all the other grains, cook all of those, add yeast and then put the finished mash into a fermenter. After about a week, it’s a corn beer, which is siphoned off into a beer still for the stripping run, during which it goes through three stages of distillation. After that, it’s siphoned off into a “spirits” still for the final distillations, which remove any remaining compounds that could negatively impact the flavor of the whiskey.

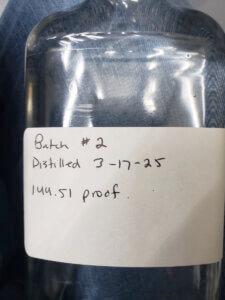

With that first run done just before Christmas, January saw us back at the farm getting more corn processed for the second run, which we completed in mid-March. Now, we’re almost finished with the components for the third run, which we plan to send to Prichard’s in the next week or two. Going forward, we’re optimistic that we’ll be able to run another batch each month during the warmer, dryer summer months, hopefully finishing before harvest time comes around again.

We had enough distillate after that first run to fill a few barrels, but, since we are making multiple runs, Seth Kimball, Prichard’s production manager, plans to wait until all or most of those runs are finished, since we’re making the same recipe every time. Then, we can sample all of the runs and blend them accordingly before we put them into barrels to age.

We’re very happy so far with the product we have (and very eager to see it barrelled). Prichard’s has been an excellent partner to work with. And while this won’t be the bourbon we plan to produce in the future, which will be distilled by us and aged in our own white oak barrels from the farm, we think it will have a distinct and delicious flavor, thanks to the farm’s springwater and Jimmy Red corn.

In the meantime, we have a lot of work in front of us. Thank you for joining us on this journey as we move closer to opening the doors of our uniquely local, farm distillery.